A Word in Edgewise

By Constance Garcia-Barrio

Films, books and ballads tell of the South during the Civil War (April 1861-April 1865), but they seem struck dumb about black women in the North during those turbulent times. However, the Quaker City has lucked out. “Emilie Davis’s Civil War, the Diaries of a Free Black Woman in Philadelphia, 1863-1865, opens a personal window to daily life in the city’s vibrant black community,” says Judith Giesberg, 52, a professor of history at Villanova University, who edited, transcribed and annotated the diaries.

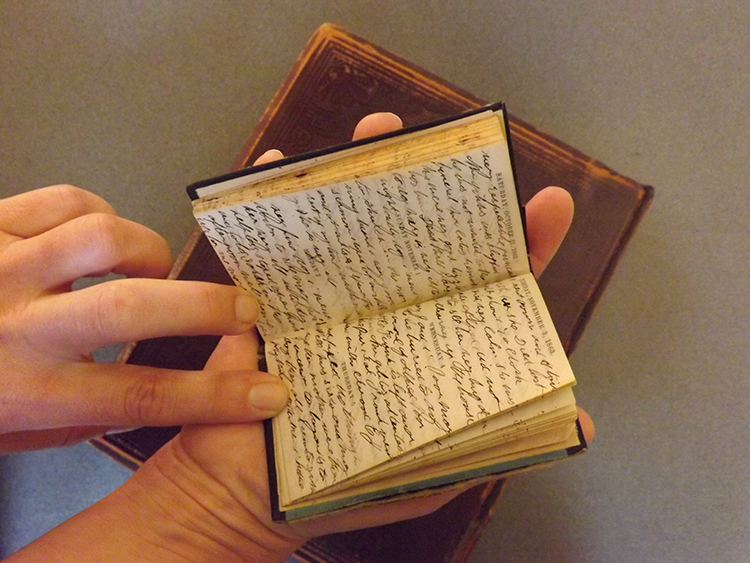

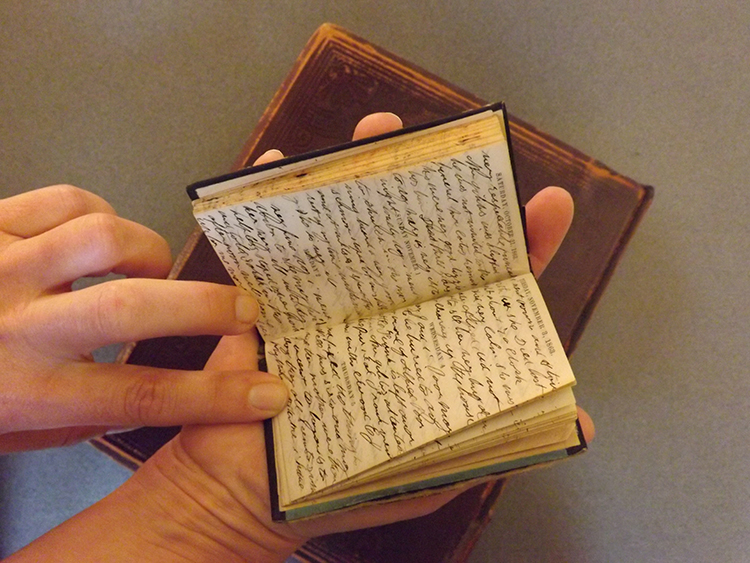

Emilie Davis (1839-1889), a lively young woman when the Civil War broke out, wrote short daily entries in three pocket-sized diaries, each no bigger than a cell phone. Giesberg’s single-volume edition preserves Emilie’s spelling and lack of punctuation.

“To day has bin a memorable day and i thank God i have been sperd to see it,” Emilie wrote on January 1, 1863. Emilie missed few big social and political events. She attended speeches by Frederick Douglass and joined other African-Americans who crowded into black churches to cheer on the stroke of midnight, when the Emancipation Proclamation became law, Giesberg explains.

A seamstress so skilled that she made wedding gowns, Emilie felt the war’s effects on cloth prices. “I went out shoping … ” she wrote on February 19, 1863, “ … muslins [a kind of cotton] are frightfully Dear … ” With the South’s disrupted cotton production and the cloth’s use in uniforms, prices soared.

The conflict sometimes changed life’s daily rhythms, as when President Abraham Lincoln proclaimed “national fast days” during the war to pray for forgiveness from God. “Today is set apart as a national fast day … ” Emilie wrote on April 30, 1863.

In late June 1863, a battle seemed to loom on Philadelphia’s doorstep, when General Robert E. Lee, desperate to take the fight out of war-weary Virginia, invaded Pennsylvania. “Refugees are comin from all the towns this side of Harrisburg the greates excitement Prevails. I am all most sick worrin about father [who lived in Harrisburg] … ” Emilie wrote on June 29 and 30, just before the Battle of Gettysburg.

“Emilie was right to worry about her father, because rebel soldiers kidnapped hundreds of free blacks and sold them into slavery,” Giesberg explains.

Pennsylvania began recruiting black soldiers, called United States Colored Troops (USCT), in 1863. Many of them trained at Camp William Penn, 13 miles north of the city in Chelten Hills (Cheltenham Township), near the home of abolitionist Lucretia Mott (1793-1880). “This morning Jenie and I went up Chestnut St. to see the colored soldiers they went away to day,” Emilie reported on February 10, 1864. Black Philadelphians applauded the troops, who would fight at Yorktown and Petersburg, Giesberg says.

Philadelphians rode a wave of joy when Richmond fell on April 2, 1865. “The city is wild with excitement,” Emilie wrote on April 4, 1865, “ … flags are flying everywhere.” Just 11 days later, news of Lincoln’s murder crushed many Philadelphians. “The city is in deep mourning,” Emilie wrote.

People mobbed the streets and stood on rooftops on April 23, 1865, to watch Lincoln’s funeral cortège inch down Broad Street, then turn east to Independence Hall, where the body would lie in state. Emilie tried to glimpse Lincoln that day but was crowded out. She succeeded the next day. “I got to see him after waiting [two] hours and a half it was certainly a sight worth seeing … ”

The Civil War had ended, yet struggles remained. Not one to miss good entertainment, Emilie and a friend went to see Blind Tom (1848-1908), pianist and composer extraordinaire, sometimes described as an “autistic savant.” Born into slavery, at age 10 he was said to be able to play two different tunes on two different pianos while singing a third song. “I was much Pleased with the preformance excepting we had to sit upstairs which made me furious,” Emilie wrote on September 14, 1865.

Black women in Philadelphia, including Emilie, continued to fight to ride horse-drawn streetcars, a battle begun during the Civil War. Some war-time camps for United States Colored Troops lay far from black neighborhoods. Determined to deliver supplies and tend to sick and wounded African-American soldiers, members of black women’s aid societies like the Ladies’ Union Association—to which Emilie belonged—at times rode horse-drawn streetcars to reach the troops. When white passengers objected, black women usually held their ground.

That stance could mean fights.

“Harriet Tubman (1822-1913), a former Union spy and scout, suffered injuries to her arm and shoulders in 1866 when a conductor and his friends threw her off a Philadelphia streetcar,” Giesberg says. Black women, who often faced these fights alone, sometimes sued streetcar companies. They helped gain ground for the whole community, and in 1867, a law ended streetcar segregation.

susie king taylor’s memoir, Reminiscences of My Life in Camp with the 33rd Colored Troops, Late 1st South Carolina Volunteers, makes a good complement to Davis’s diaries. Born into slavery in South Carolina, Taylor (1848-1912) became literate because her enslaved grandmother sent her to an illegal school for black children. “We went every day … with our books wrapped in paper to prevent the police or white persons from seeing them,” Taylor wrote.

Thanks to that schooling, Taylor described not only the lice, hunger, wounds and celebrations among black Union troops in the South—“On the first of January 1863 … we had a grand barbecue … A number of oxen were roasted whole … ” —but also the little-known help Union soldiers received from southern black women during the war.

“Many people do not know what some … colored women did during the war,” Taylor wrote, “ … hundreds of them assisted … Union soldiers by hiding them and helping them escape. Many [black women] were punished for taking food to the prison stockades for … [Union] prisoners … The soldiers were starving, and these women did all they could toward relieving the men, though they knew the penalty, should they be caught … These things should be kept in history before the people.”

I want more. Are these memoirs for sale?

Yes! Here’s the link to buy hard cover and soft cover:

http://www.psupress.org/books/titles/978-0-271-06367-6.html

You may also want to take a look at "Notes from a Colored Girl: The Civil War Pocket Diaries of Emilie Frances Davis (Women’s Diaries and Letters of the South)," by Dr. Karsonya (Kaye) Wise Whitehead. It received the won the Darlene Clark Hine Book Award from the Organization of American Historians and in 2014, it received the Letitia Woods Brown Book Award from the Association of Black Women Historians.