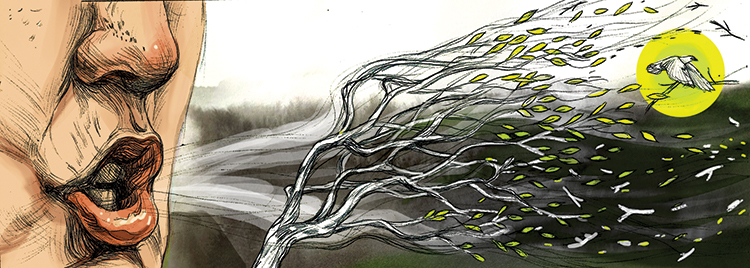

Illustration by Abayomi Louard-Moore

Politics as Usual

by Jerry Silberman

Question: What political program will best help limit the effects of climate change?

The Right Question: Why should we think politics is a way to address climate change at all?

Politics comes to us from Aristotle, who attempted in his treatise titled “Politics” to determine the best way to govern a city-state, surveying the history and world experience available to him. In Aristotle’s world, the inequality of people was a basic assumption: Some people were born to be slaves; men were destined to rule over women; elite “citizens” governed, to the exclusion of tradesmen and small farmers.

Citizens also had access to society’s surplus, which, in the absence of fossil fuels, were minuscule compared with ours, but still substantial enough to sustain intense intellectual activity within a small elite—and to build architectural monuments we still revere.

Today, the English translation of Aristotle’s “Politics” is in the public domain and can be downloaded by anyone reading this column. In his day, only a few copies of his work, laboriously copied by hand, were available to members of his class and were preserved through the generations in part by luck and in part because of the discipline of devoted preservationists. Now, in stark contrast, billions of words hit print (or cyber print) each day, virtually all of them destined to be forgotten within the lifetimes of those writing them. Our society is aggressively ignorant of the past, and also in our conviction of superiority to all that has come before us.

Today, politics refers to the methods of exercising power in the realm of government, and the means of achieving a position to exercise such power. Barack Obama, Vladimir Putin and Mohammed bin Salman (deputy crown prince of Saudi Arabia) are all politicians, and even bin Salman, born into the family that is absolute ruler of the world’s richest petro state, still had to engage in politics to ensure his position.

So, how much power do they have? How much real choice in public policy? To which citizens are they accountable if they seek to remain in their position? Finally, how do the answers to these questions affect their ability to respond to climate change?

Economic power in the modern industrial world is extremely centralized, which is only possible with an enormous communications and transportation infrastructure. Military might, the ultimate symbol of state power, both protects and is entirely beholden to the corporate-owned and centralized infrastructure: Lockheed Martin and a handful of corporations dominate weapons production; AT&T, Verizon, IBM and a few more own the computers that keep the internet going; the pipelines and railroads that move oil and gas around the country are all privately owned, such as CSX, which runs oil trains into Philadelphia.

Obama, Putin and bin Salman, by different mechanisms, are dependent on the tiny global elite who hold economic power through ownership of the infrastructure. They don’t necessarily perceive this as dependence because of their shared values, and because the dependence is mutual. The legitimacy of the state, which Obama, Putin and bin Salman all symbolize, is essential for business as usual to continue.

Corporations such as Aramco, ExxonMobil, Microsoft, Apple, Nestlé and GE each have a greaterdirect impact on the world economy than most countries. Collectively, they sustain the global infrastructure across political boundaries and exist symbioticallywith Obama, Putin and bin Salman.

According to Aristotle, politics is about managing relations between groups of people who have some common interests. Today, politics, in its many varied faces, serves one goal: to maintain the economic stability of the world on behalf of the profits of its corporate sponsors. Follow the money, and seemingly irreconcilable differences in political systems fade into a sideshow. An example: ExxonMobil continued its joint exploration work with Russian fossil fuel companies without interruption by the U.S.-urged boycott of Russia after the Ukrainian debacle began.

The system is showing severe strain as a result of increasingly scarce resources and its own byproducts—pollution and climate change. It remains intact because the values that serve to entrench the power of economic elite—perpetual growth, consumption as the key index of human achievement and faith in technology to solve any problem we conceive of that interferes with the first two—continue, surprisingly, to be widely believed by masses of people to whom they bring neither power nor happiness.

Repudiating these values means repudiating “politics as usual,” regardless of the system, or the party, or the country. Neither Obama, Putin nor bin Salman will distance themselves from those values, despite the different narratives they offer on climate change. Neither will Bernie Sanders or Donald Trump.

There are other core values around which we must build our lives and societies if we are to mitigate climate change: reducing consumption, shrinking our population and working toward a steady state economy at a level consistent with the annual solar budget. Until significant numbers of people withdraw from the current value system and support for the economic powers that foster them, competing political programs will not offer effective strategies to minimize climate change.

Jerry Silberman is a cranky environmentalist and union negotiator who likes to ask the right question and is no stranger to compromise.