Story by Jacob Lambert | Portrait by Gene Smirnov

Story by Jacob Lambert | Portrait by Gene Smirnov

Iris Marie Bloom is busy. Seriously busy. The night before we meet near her West Philadelphia home, she was in Warminster, screening a documentary and organizing residents. Three days before, she was at a rally in Harrisburg. As we talk, she occasionally checks the time; she has another interview that morning, and after that, her weekly radio show.

“I’ve been working 17-hour days,” she says, smiling over her coffee.

Her hazel eyes, however, show little sign of fatigue. She sits straight in her chair, articulate and focused. File folders, filled with articles and fact sheets, are neatly stacked at her elbow. For someone who works so hard, Bloom seems perpetually energized.

Those endless hours of work — interviews, research, articles for the University City Review and Weekly Press, radio broadcasts, organizational minutiae, long drives through the night — are waged in an attempt to counterweigh Pennsylvania’s natural-gas boom, which Bloom, 50, sees as an environmental threat unlike any the state has known. As the director of Protecting Our Waters, a grassroots group founded in late 2009, she is a leading advocate of slowing down a process that has spun out of control.

“[Natural-gas drilling] is such a huge issue that it’s taking all of our resources and all of our time,” she says. “It’s top priority.”

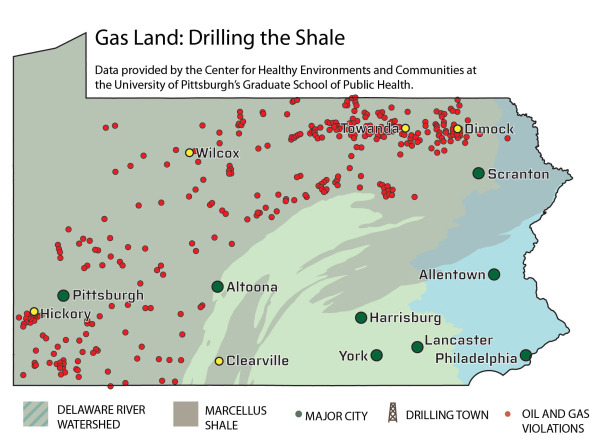

Sixty percent of Pennsylvania lies above a rock formation known as the Marcellus Shale. It’s rich in gas accessible only through a process known as hydraulic fracturing, or “fracking.” In 2008, the Department of Conservation and Natural Resources leased 74,000 acres of state forestland to a throng of oil and gas companies, all of them eager to drill.

Fracking, which for shale has only recently become economically viable, forces water, sand and chemicals deep into the ground; the pressurized materials then blast the shale apart, releasing the gas within. In the past three years, 2,400 such wells have sprouted across the commonwealth, and thousands more have been granted permits. And while gas companies expend great effort promoting fracking’s safety, in 2009, ProPublica found “more than a thousand reports of water contamination from drilling across the country” and “dozens of homes in Ohio, Pennsylvania and Colorado in which gas from drilling had migrated through underground cracks into basements or wells.”

Despite such dangers, in Pennsylvania “there are no requirements for chemical disclosure; no requirements for greenhouse gas emissions,” says Bloom. “We’re fighting for more public comment and more public hearings.” Perhaps most crucially, Protecting Our Waters supports the extension of a Delaware River Basin Commission (DRBC) moratorium — the deadline for public comment is, at present, March 16 — on drilling in the Delaware Watershed until thorough environmental-impact studies are conducted.

“[Drilling] is being done in a big rush because it’s underregulated,” she says, “and that’s the problem.” With Republican Governor Tom Corbett — who as a candidate accepted $1.2 million in gas-industry donations — now in power, she adds, “I think there is very little chance of getting anywhere near adequate regulations.”

Real-world problems brought by this laxity are already beginning to mount. Spills of salty, toxic wastewater — a nasty byproduct of fracking — have become almost routine; one company, Atlas Resources LLC, was responsible for seven spills and several other violations between December 8, 2008, and July 31, 2009. When wastewater isn’t being spilled, it’s allowed to be partially treated and dumped into waterways, despite uncertainty as to the practice’s safety. In January, the Associated Press reported, “Of the roughly 6 million barrels of well liquids produced in a 12-month period … the state couldn’t account for the disposal method for 1.28 million barrels, about a fifth of the total.” What’s more, also according to the AP, “Regulations that should have kept drilling wastewater out of the important Delaware River Basin, the water supply for 15 million people in four states, were circumvented for many months.” As a likely consequence, many state waterworks now struggle “to stay under the federal maximum for contaminants known as trihalomethanes, which can cause cancer if swallowed over a long period.”

And people are getting sick. Thanks to its starring role in the Josh Fox documentary Gasland, the town of Dimock in Pennsylvania’s northeast corner has become notorious for its tainted aquifer. A June 2010 Vanity Fair article (“A Colossal Fracking Mess”) described a place in which “people’s water started turning brown and making them sick, one woman’s water well spontaneously combusted, and horses and pets mysteriously began to lose their hair.” The piece summarized the fears held by Bloom and those of similar concern: “The rolling hills and farmland of this Appalachian town are scarred by barren, square-shaped clearings, jagged, newly constructed roads with 18-wheelers driving up and down them, and colorful freight containers labeled ‘residual waste.’ ”

Bloom has witnessed such scenes. She’s been to Dimock and also to Hickory, home of fish kills, cattle deaths and ruined farmland. She’s been to Clearville, where one woman told of having her yard coated by an “unknown substance” that spewed from nearby gas-processing equipment.

“The company came out, cleaned it and paid her for her vegetables — but they never told her what the substance was,” Bloom says, incredulous. “When you have the level of secrecy and unresponsiveness that’s endemic in this industry, these kinds of ‘events’ symbolize the powerlessness that people feel when they’re up against these companies.”

This theme — the plight of common people in the face of callous authority — has been a constant for Bloom. Born in El Paso, Texas, she grew up in northern Virginia before attending Wellesley College, in eastern Massachusetts. English degree in hand, she made her way to New York, where she began a life in activism.

“I’ve always cared about big-picture issues,” she says. “War, peace, justice, the environment.”

She worked with the American Committee on Africa and the War Resisters League before moving to Philadelphia in 1989. In the mid-’90s she founded and developed WAVE (Women’s Anti-Violence Education), a women’s self-defense program that continues today.

Bloom’s work at WAVE was emotionally wearing, and after 15 years, she says, “I needed to fall in love with the world again. So I became a sailor.” She laughs. “Cheap little boats, but big adventures.” Bloom navigated the Delaware River and the Chesapeake Bay, sailed down to the Bahamas. She outran ocean storms and rode alongside dolphins. These hours spent at the tiller, observing the tides and fish, brought about a passion for water — and steered her toward a new career.

Her subsequent study of the region’s waterways attuned her to their precariousness. “I was really devastated by the state of emergency that the Bay was in,” she says of the Chesapeake, which has been in decline for decades.

Her concern led her to a conference organized by the Chesapeake Bay Foundation in May 2009. “I had never heard of Marcellus Shale or fracking,” she remembers. “But there was a keynote address by [then-secretary of the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection] John Hanger. He said in a thundering voice that [fracking] was the biggest environmental issue of our time.” She shakes her head. “Someone yelled from the back of the room, ‘Then why are you letting it go forward?’ ”

This institutional hypocrisy, combined with her nascent love of water, propelled her. “I started to dig into it, and I was horrified,” she says of her research, which expanded to include the Delaware Watershed and the damage that drilling would bring. “We’ve fought for decades to clean the Delaware … so why should we pollute it now?” She asked a friend at the National Park Service if Marcellus drilling was as potentially disastrous as it seemed. “I asked him, ‘Is it true? Is it as bad as it looks?’ He said, ‘Yes, be afraid. Be very afraid.’”

Despite such warnings, Bloom’s colleagues describe her as fearless — or rather, as Anne Dixon, a Protecting Our Waters volunteer, puts it, “Everyone has some fear, but she puts it aside quite well. She’s very tenacious.”

Denise Dennis, an historic preservationist from Northeast Pennsylvania, says, “I really admire what Iris is doing; she’s way out on the forefront on this. She has the courage of her convictions when it’s not the easy thing to do.”

Jerry Silberman, another volunteer, says, “Iris has more information on the tip of her tongue on this than anyone I know. She’s an exciting person to work with because she’s always upbeat and her energy is infectious.”

Indeed, Bloom exudes a controlled determination, a warm and eager drive. She knows what she’s up against — gigantic corporations, acquiescent legislators, a statewide hunger for jobs — yet she feels compelled to resist. She tells me of deaths in Colorado, possibly due to fracking, in a tone of rational outrage. At one point, while discussing a family so wracked by gas fumes that their noses wouldn’t stop bleeding, she had to gather herself. She takes these wrongs personally.

“It’s about people,” she says of her work. “As I’ve traveled across Pennsylvania, it’s so clear that rural people are feeling abandoned and unprotected.” Those least able to afford the costs of drilling’s fallout are the same people who will, in the months and years ahead, find themselves most affected. As with war, apartheid and sexual assault, “It’s a justice issue. It’s part of what’s kept my motivation so intense.”

For many Philadelphians, natural-gas drilling and its attendant ills might seem a distant matter. Of the 2,400 new wells, the nearest to Philadelphia is in Columbia County, 90 miles away. Few city dwellers have likely heard of drilling towns like Towanda, Wilcox or Ward. Yet the Delaware Watershed covers the state’s urban southeast as much as its rural northeast, and gas extraction in the latter could ultimately impact both. With that in mind, Bloom began educating City Council members, notably Curtis Jones, Jr. and Blondell Reynolds Brown, on the issue late last winter. Before Bloom’s arrival, she says, it seemed that “nobody in City Council had heard of fracking.” Which made it all the more impressive that late this January, Council unanimously passed Resolution 100864, which, among other recommendations, urged the DRBC to disallow drilling in the watershed until proper “cumulative impact studies … are completed, assessed, and publicly debated.” While the recommendation is not binding, it adds a strong official voice to the ranks of fracking opponents — and was a heartening validation of all Bloom strives for. Thanks in large part to her, the City of Philadelphia has, in her words, “embraced the ‘precautionary principle’: Until something is proven safe, it shouldn’t be done.”

As our interview winds down, Bloom mentions Wyoming, where a decade of citizen action resulted in a law requiring chemical disclosures by natural-gas companies.

“What about you?” I ask. “Would you spend 10 more years on this?”

Without hesitation, she responds: “Oh yeah. I have no choice; we have no choice. We have to fight.”

She leans forward slightly, adding,. “What we need is for everyone that’s reading this article right now to call their state representative and their state senator and demand that there be a moratorium on gas drilling.”

She looks at my pad as I try to get it down.

“Do you think you can write that?” she asks.

I smile and say that I’ll see how the piece goes, if I can find a place for her entreaty. Considering Iris Bloom’s unflagging, hopeful effort, the favor seems to be the least that I can do.

GET INFORMED, GET INVOLVED:

“Frack Radio,” Bloom’s weekly program: wfte.org

Protecting Our Waters: protectingourwaters.com

Delaware Riverkeeper Network (another activist group): delawareriverkeeper.org

FracTracker, a project of the Center for Healthy Environment and Communities: fractracker.org

I have done a little bit of research on fracking, and it seems like it works pretty well. I agree that it isn't something that should be done near homes. I guess that is why a lot of fracking goes on out in the middle of nowhere. I think fracking has helped the drilling industry a lot though. There are only so many people that need water wells drilled. But I guess building will always need drilling done for the foundation. http://www.brewsterwelldrilling.com/en/caissons.htm

I have done a little bit of research on fracking, and it seems like it works pretty well. I agree that it isn't something that should be done near homes. I guess that is why a lot of fracking goes on out in the middle of nowhere. I think fracking has helped the drilling industry a lot though. There are only so many people that need water wells drilled. But I guess building will always need drilling done for the foundation. http://www.brewsterwelldrilling.com/en/caissons.htm

Nice read, I just passed this onto a colleague who was doing a little research on that. And he actually bought me lunch since I found it for him smile So let me rephrase that: Thank you for lunch!