Photo courtesy of Kevin Roth

By Francesca Furey

It all started with a conservation group’s angry intern.

In the winter of 2018, employees of the Izaak Walton League of America, headquartered in Gaithersburg, Maryland, were greeted by an unsightly pile of salt. It obstructed part of the driveway and sat on top of a storm drain. It wasn’t just huge, it was a hazard—for drivers and the environment.

As Scott Maxham, the League’s Clean Water Fellow, prepared to head outside to clear the pile, his colleagues stopped him. It would be too risky, they said; the driveway was adjacent to a four-lane road.

“We were like, ‘You can’t do that, it’s a very busy road. You will get killed,’” says Emily Bialowas, the League’s Chesapeake monitoring outreach coordinator. “So, he got really riled up.”

Maxham tried to track down city and county agencies for salt cleanup, and came up short. The pile of salt was leaking chloride and other harmful chemicals into a creek on the property.

The League knew this wasn’t the only instance of over-salting and began connecting citizens at regional watersheds and organizations to look at the impact of this practice on water quality.

Photo courtesy of Kevin Roth

Thus, the Winter Salt Watch was created. It was a natural fit for the League, which dedicates itself to the conservation, restoration and promotion of sustainable practices in natural resources. Founded in 1922, it prides itself on being a defender of soil, air, trees, wildlife and water—the last of which can be easily polluted by road salt.

Road salt, which is sodium chloride, was first used in 1938 to de-ice roads in New Hampshire, according to the Cary Institute of Ecosystem Studies. Four years later, in 1942, 5,000 tons of salt blanketed highways across the United States. That number has since skyrocketed to 10 to 20 million tons of salt annually.

On average, about 844,000 tons of road salt were used on Pennsylvania roads in the last five years, PennDOT reported.

High quantities of road salt can build up in streams, lakes, reservoirs and watersheds, and harm aquatic plants and animals. It can also contaminate drinking water and damage infrastructure.

A body of freshwater should never exceed 1,000 parts per million, according to parameters set by the U.S. Geological Survey. Levels of 230 ppm or more can be toxic for aquatic life.

“The fish that live there and the aquatic macroinvertebrates … can’t handle salt. And any mammals that drink out of the stream, they can’t really handle salt,” Bialowas says.

If the saline level is higher than normal, it’ll eventually impact humans because it goes into our drinking water, but not as “immediately and dramatically” as it does for aquatic wildlife, Bialowas adds.

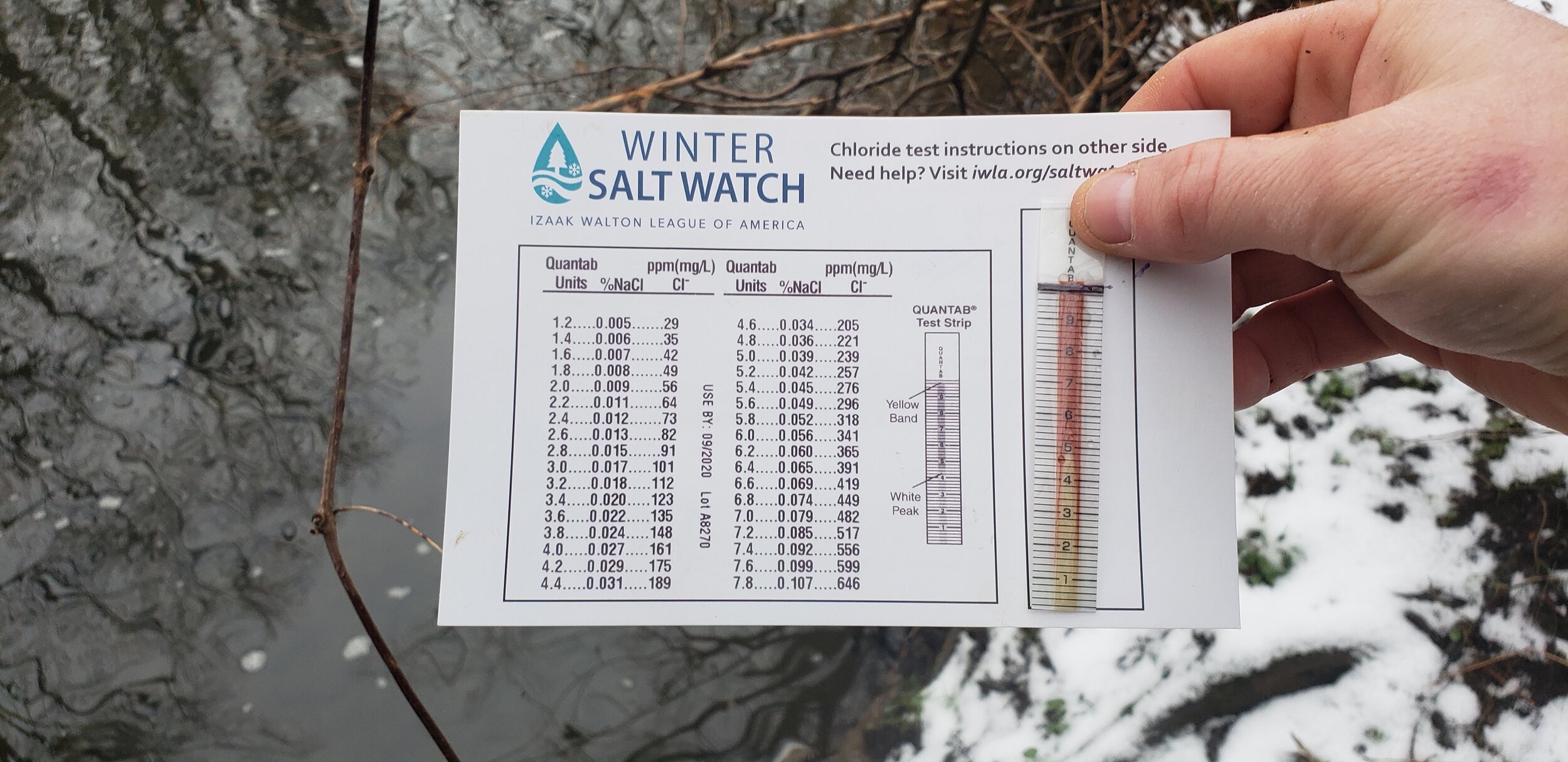

Using the help of citizen scientists, the Winter Salt Watch monitors these fresh waters. The program provides organizations along the East Coast, plus Minnesota and Michigan, with test kits to check chloride levels. Then, citizen scientists upload their findings on the Water Reporter app, allowing the League to identify patterns and locations of abnormal levels.

Tookany/Tacony-Frankford watershed partnership conservation leader Ryan Neuman says this data collection is important work.

“With the citizen science effect, we can get a lot more data points,” Neuman says. “There wasn’t a lot of this representative data of the whole watershed.”

Other active organizations that test waters monthly in the region include the Lower Merion Conservancy and the Coalition for the Delaware River Watershed.

Photo courtesy of Kevin Roth

Some have even detected extreme levels, like the Darby Creek Valley Association, which reported results of 482 ppm, 583 ppm and 800 ppm throughout its watershed tributaries on March 4, 2019.

Kevin Roth, the education and outreach coordinator at the Pennypack Ecological Restoration Trust, says the Pennypack Streamkeepers began to participate in the Winter Salt Watch after chloride sensors at Pennypack Creek “went crazy,” in November 2018. These levels followed a random snowstorm that hit the Philadelphia region that came too quickly for trucks to salt the roads.

Homeowners, however, were prepared.

Most residents over-salted their driveways, walkways and sidewalks. Once the storm cleared, the remaining salt leaked into the creek and tripled its chloride levels.

Soon after, a group of 20 to 30 streamkeepers conducted 60 reports.

“We found exactly what we expected,” Roth says. “Salt content in Philadelphia-area creeks were way higher than sustainable because freshwater shouldn’t have any salt at all. We had reports starting at 230 ppm of chloride in the water.”

The dangerous results inspired the Pennypack Trust to hit the ground running and try to tackle salting methods in their community by educating the public about chloride contamination and recruiting more citizen scientists along the way.

A small amount of salt isn’t too dangerous, Roth says, but constant oversalting by homeowners is—and this is something residents need to learn. Roth and his partners at Pennypack Trust decided to implement a three-year plan to promote awareness about proper salting techniques. Bialowas says the folks at Pennypack propelled the mission of the Winter Salt Watch and went above and beyond.

Through current community programs and social media campaigns, Philadelphia-area organizations are teaching homeowners how to properly prepare for snow storms.

“A lot of them salt the wrong way. They kind of just throw it out before the snow, and then they throw it on top of the snow. They think it’s a be-all, end-all,” Roth adds.

Homeowners can follow four different steps in decreasing their salt pollution, according to the Tookany/Tacony-Frankford Watershed:

-

Shovel before you salt to decrease the amount used.

-

Use just enough salt to melt ice, and sweep up any leftover salt for reuse.

-

Avoid products with urea, such as kitty litter or ashes.

-

Educate neighbors and alert the township of any salt pile-ups.

“We’ve been focusing on telling the public to use less salt and clean up after themselves after a storm,” Roth says. “Unfortunately, salting is a part of what we do now because of insurance, legality and safety. Obviously, we’re not against safety, but we definitely can be doing better.”