Illustration by Corey Schumann

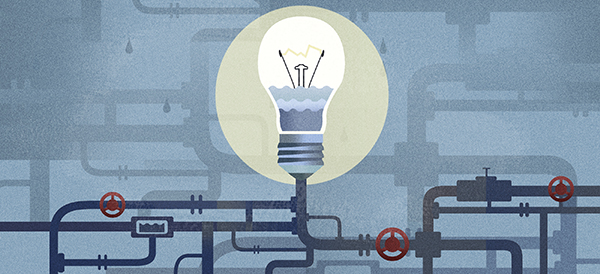

Water, Water Everywhere

by Jerry Silberman

Question: How can I reduce my personal water consumption to protect the environment?

The Right Question: How can I reduce my energy consumption to protect fresh water?

Kayaking down the Schuylkill a couple of weeks ago, in the zone of cool air just above the surface of the flowing water and dipping into the river when I felt the urge, it was hard to think about being short of water. Even after two weeks of intense summer heat and barely any rain, very little soil showed on the banks, indicating the river was not seriously low.

But, in fact, shortages of safe drinking water may be a bigger factor in the decline of industrial civilization than collapsing oil supplies. Oil supplies will likely start to collapse in three to four years, but access to drinking water is already a problem in many areas of the globe, including major cities in China.

There has been a significant rise in personal water use in industrialized countries. Skyrocketing human population is part of the problem. Each person needs water for personal use, but, unfortunately that’s not the main issue: The real explosion in fresh water use has been in power generation, irrigation and resource extraction.

These three major industrial processes, which we don’t normally see and therefore take for granted, are the bulk of our water use. We use enormous amounts of water for power and industry, we destroy aquifers through irrigation, and we further reduce available water when we extend our built environment into areas that were formerly absorbing water and recharging our aquifers.

How much water are we using? The Union of Concerned Scientists (UCS) has a fact sheet with some startling numbers, titled “The Energy-Water Collision: 10 Things You Should Know.” It shows that these industrial processes use magnitudes more fresh water than we use in our homes for drinking, cleaning and for yard use. (Which is not to say that we shouldn’t try to put an end to watering millions of acres of toxic lawns.)

According to the UCS report, in the Southeast United States, two-thirds of all withdrawals of fresh water are for use in power-generating plants. What that looks like individually is that an average family of four directly uses about 400 gallons of fresh water per day.

But when you consider their indirect use (the water withdrawn for use at the local power plant) the family actually uses 600 to 1,800 gallons.

Alternative fuels appear to consume much more water than fossil fuels, particularly irrigation-intense ethanol. The comparison, however, likely doesn’t take into account the relatively recent rise of fracking, which now accounts for a majority of our natural gas and at least one-third of our oil; it’s a hugely water-intense process that has the added insult of rendering some of that water unusable.

In addition to mine drainage and fracking, we must also consider other industrial processes that render water and groundwater toxic for generations.

While Pennsylvania’s Department of Environmental Protection now has drought watches up in 34 counties, withdrawals for fracking are unaffected.

At least for water used for cooling at power plants, the use is more short-term. As outlined in the UCS report, we use water, for instance, to cool the steam that powers electricity-generating turbines. This water, for the most part, remains within the hydrologic cycle and is available for other uses. Conversely, water released to the environment after being used to cool nuclear power plants is often dangerously warm for fish and other life in streams and rivers.

These myriad questions all get to the life cycle consumption of water in industrial processes, which has not been examined as carefully as life cycle energy consumption—but it’s imperative that we take a closer look.

In my own personal quest to use less energy and water, understanding the enormous consumption of water in generating electricity sinks the idea of electric cars, although a lean and efficient electric streetcar could move people with a fraction of the energy that goes into powering individual cars.

But if you feel you must do something, a simple decision to turn off your air conditioner will reduce your water use much more quickly than, for instance, installing a low-flow toilet in the house.

It will also reduce your contribution to greenhouse gases, the effect of which the air conditioner seeks to mitigate even as it simultaneously aggravates the original problem by using more electricity: It’s not exactly a virtuous cycle.

While we study this problem more closely, I propose a solution.

As the Greenland ice sheet melts, billions of gallons of fresh water are being freed up for the first time in millennia. Perhaps the oil pipeline builders are missing an opportunity? If we could build a pipeline from Greenland to Arizona, people in Phoenix could grow all their own vegetables locally!

If my solution sounds ludicrous, it is.

A water pipeline and a natural gas pipeline have an equal chance of keeping climate change in check and our sea levels from rising. For that, we’ll all need to live lives in which we consume less—directly and indirectly.

Jerry Silberman is a cranky environmentalist and union negotiator who likes to ask the right question and is no stranger to compromise.