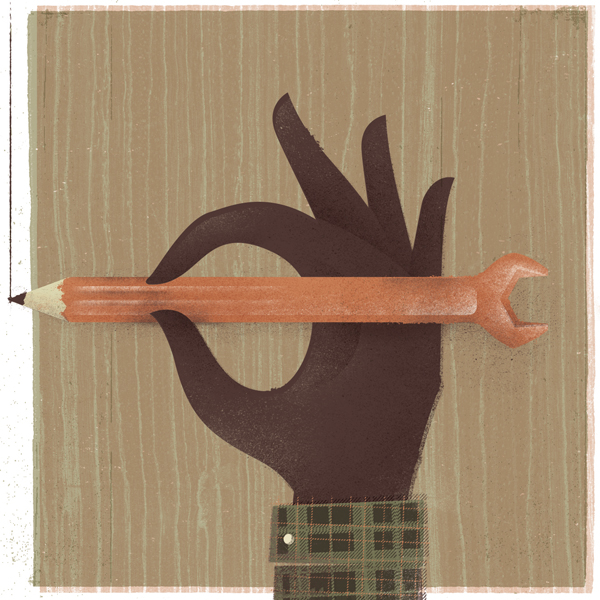

Illustration by Mike L. Perry

The Makers are Coming

Interview by Heather Shayne Blakeslee

Fifty years ago, factories were busily producing products that America was exporting around the world. Since then, we’ve outsourced much of our making and doing. “Makerspace” is a catch-all term for places where inventors, tinkerers and hackers—makers all—can gather. These collaborative workspaces can be for-profit companies, nonprofit organizations, or even hosted by a public institution—such as a library—that offer access to industrial tools like mills and lathes, 3D printers and commercial-grade sewing machines. Regardless of the business structure, any makerspace is designed to foster innovation and offer open access to tools and resources for the do-it-yourselfer.

Makerspaces are reigniting a desire to design tangible goods—many of them invented to help solve environmental and social problems—and then make them in America. Mark Hatch, author of The Maker Movement Manifesto, is also the CEO of TechShop, a growing San Francisco-based company that operates nine such spaces around the country.

You write in The Maker Movement Manifesto, Call it what you will: the next industrial revolution, the maker movement, the creative revolution. History will name it once it’s over.

MH: I prefer “the creative revolution,” because in the process of democratizing the tools, a broader array of people are going to have access… The movement is really coming out of what I believe is the human spirit and interest in making things. It’s fundamental to what it means to be human. The opposable thumb and making tools is often ascribed to what it means to be human. But then there is the question, “So what? What do you do with those thumbs? What do you do with those tools?” What you do with those tools is create things …

The movement itself is a reemergence of craft from the turn of the previous century where people got interested and excited about making things again. Whether it’s an entrepreneur or an artist, or an educator or even just a tinkerer, [it’s] the joy of doing, essentially re-found and then shared. It’s infectious joy to make things, then show other people that they can make things.

We are still cleaning up some of the environmental damage of the first industrial revolution and our current manufacturing processes. Do you see greater consciousness now about resource extraction, manufacturing impacts, life cycle analysis, materials toxicity?

MH: [According to an independent survey by BMW] 30 percent of the projects being made at TechShop were explicitly designed to resolve societal issues, sustainability—recycling and so forth—and that a much larger percentage had embedded those principles into the production of what they were trying to do. That is really exciting.

The maker movement isn’t just about being able to print 3D custom key chains with your baby’s face on them at home.

MH: Right. [One product example] is a nitrogen detection product that figures out how much fertilizer—nitrogen—is in the soil. At the beginning of the planting season, it does it meter by meter, across the entire crop field. So, then you adjust your fertilizer accordingly, meter by meter and by doing so, the farmer saves a lot of money on fertilizer, and—more importantly—by not over-fertilizing, there’s not as much runoff that goes into the rivers, [creating] a massive death zone that we have at the end of the Mississippi.

I also read that some of the access to machines and processes that allow for really rapid prototyping can eliminate waste.

MH: The more iterations you can run on the prototype, the more effective your waste management and sustainability capabilities are. If you only have six weeks and you can only take time to do two or three prototypes, it’s just not as effective as doing 60 and really working the problem. There is a little more waste on the front end, but it saves a lot on the back end.

In Philadelphia, some critics have characterized the maker movement—dismissed them—as a bunch of mainly affluent white guys fooling around. You believe the largest untapped resource on the planet is spare time, creativity and the disposable income of the creative class. Is the truth somewhere in the middle?

MH: Yes, it is. I guess it’s a fair assessment to say that it is higher income … but it’s a little unfair to say that it’s all the fault of the movement. The movement [has] emerged in a society that is ignoring [social problems] …

[At TechShop] I can’t tap into the local public school educational institution infrastructure to get kids to catch up. I want to; we give free tours. We would love to have them there. But [the schools] have other priorities. Until those priorities change, there’s not a lot that I can do to get kids there.

You believe American institutions are failing to graduate enough engineers and scientists—and that economically this is “insane.” How must we change the education system to get people more accustomed to the idea that this is something that they can do, whether they are a boy, girl, person of color, man, woman, child or retired person?

MH: We have [designed] our entire [eighth through 12th grade] system around a lie that everybody has to go to college. … Everybody doesn’t have to go to college. … Where are all the tools, where’s the education in order to help those who aren’t going? The answer is we ripped all those tools out and sent them off to the junkyard when the industrial art instructor retired.

It’s going to come back. It’s going to come back because the colleges are going to make the adjustments. You are going to need to have these skills to get into college, and these are definitely the same tools that employers need. The educational institutions are going to become more project-based … [classrooms with] a lot more hands-on work, and [where] more kids are teaching kids, and mentors are involved, and it’s less of spewing knowledge and more of collectively learning knowledge. I think that’s coming.

You also mentioned that the federal government is interested in creating some new advanced manufacturing research and development efforts at universities around the country, but you have concerns about how that’s implemented, and whether or not more people than just a very, very select few researchers will have access to that equipment.

MH: It’s an unmitigated tragedy, a disaster. We spend billions of dollars at universities, which is fine—they do great research—but, you know, a portion of those publicly provided funds go to acquiring equipment that can only be accessed by the few people authorized. That’s got to stop …

I’m just really talking about mills, lathes and laser cutters. … [They] are the backbone of any mechanical engineering department, art department, architecture department, physics department, chemistry department. [They] are used only a few hours a day, and sometimes a week. You walk around a university at five o’clock at night, you know, these classrooms are empty, the tool rooms are empty.

Whereas, if you walk into any kind of makerspace there is always activity going on?

MH: It’s jammed! There are lulls in the morning time. … By 2 o’clock in the afternoon, things are jammed and they become a social center. We’ve got to be running—I don’t know—20 different kinds of events in San Francisco on a monthly basis? From date night to women in engineering, the electronics meet-up, the robot meet-up … it’s wonderful.

You wrote that something magical happens when 300 people or so join a makerspace.

< p>MH: They spark more creative collisions. … It’s a combination of collisions in a friction-free environment … a magnetic environment. … You are more likely to get access to the same space at the same time as somebody else that is working on the same kind of problem … they will geek out for hours. What these spaces do … is create a commons that allows them to have those interactions. It’s not that [the people there] are smarter; it’s just that they are in the right place at the right time, often by intent.

There are pieces of this movement that will allow for more local manufacturing—but you note that there are products we are producing faster and cheaper overseas. Do you see that changing as America retools itself and understands what this opportunity is, or is China just always going to be ahead of us in that regard?

MH: China has some fundamental advantages now that they built over the last 30 years, and specifically it’s the ecosystem of components and design and supply chain. The Shenzhen area is unmatched. … But having said that, as I pointed out in the book, I truly believe big chunks of the economy are going to shift back to local manufacturers.

When we talk about manufacturing, most consumers instantly think of iPhones and millions of millions of something. But shirts are produced one at a time, typically, by hand. When you have a robot that can do that, why do the manufacturing in China when you can just do it locally? Why ship the cotton over there?

In your nine-point manifesto you say that we should “make, share, give, learn, tool up, play, support and change.” There is a lot of language about the act of making being essential to who we are as human beings. So, what’s the nexus in the creative movement where creating jobs and making money coexist with changing the world and changing ourselves?

MH: Some of it historically has been bad, right? We started making, we started extracting the materials and polluting the world in order to create an economic system. … But now, the tools, the political will, the sociological will [are there]. We are understanding [the] impact it has and we are discovering that we can actually in many instances—and I actually say in most instances—we can produce things in a way that is much more sustainable.

Mark Hatch is the CEO of TechShop and the author of The Maker Movement Manifesto.